Agriculture in Canada is a 49 billion dollar industry, and more and more Indigenous communities are exploring ways to participate in it. From large-scale production to value-add processing and community gardens to traditional medicines, how a First Nation returns to agriculture or finds a way into it will be unique to every community. But benefits are there for those interested, and the co-op model has a role to play in ensuring they do.

A survey by Farm Credit Canada

Farm Credit Canada (FCC) recently completed a survey on Indigenous Agriculture in Canada. The report on the survey has a variety of insights, from what aspects of agriculture First Nations consider most important to the types of training needed for communities to succeed. Director of Indigenous Relations at FCC, Shaun Soonias, says a key takeaway from the survey is that “85% of Indigenous communities are looking at how to get into or expand their agricultural efforts.”

Pictured: FCC Staff Shaun Soonias

A History of Broken Promises

Historically, many First Nations have agriculture experience, but a lot have lost that knowledge in the past 80 to 100 years. In Treaty Promises, Indian Reality: Life on a Reserve (2005), Harold Lerat describes his ancestors’ journey from thriving nomadic peoples near Cypress Hills to successful farmers as Treaty people on Cowessess First Nation (Treaty 4). He also outlines Canadian officials’ harsh response to this success.

The threat First Nation success in agriculture posed to settler farmers surrounding the reserve led to aggressive behaviour from Canadian officials and settler communities. They frequently broke Treaty promises – promises that include agricultural knowledge, domestic animals, and equipment – to hinder and undo this success.

Along with broken promises and actively disrupting Cowessess’ agricultural success through permission slips for produce and questionable surrender of land came a systematic effort to eliminate tradition and culture through the pass system, residential schools, and Indian agents. Alongside this cultural genocide came the loss of knowledge in agriculture.

A Return to Agriculture

“Lots of our communities have been out of ag for so long that the people who know how to farm are 80 or 90 years old. They’re not getting in a combine any time soon,” said Soonias. “Ultimately, we’ve got to revitalize our knowledge and capacity in the sector.”

Still, there are great opportunities in the industry, and communities – such as Thunder Farms on Thunderchild First Nation – are finding ways to participate in the industry.

In 1992, Thunderchild First Nation purchased over 6,100 acres from farmers through the Treaty Land Entitlement Agreement. For years, the First Nation leased the land back to farmers, often tax-free. When the leases came up in 2016, Thunderchild took the opportunity to start farming.

“In the past, it’s always been the Elders’ advice for Thunderchild to farm its own land,” said Linda Okanee, director of operations for Thunderchild First Nation in an Eagle Feather News article at the time. “The leadership has always had that in the back of their mind and the opportunity came about and decided to do that.”

Our Youth is a Competitive Advantage

CREDIT: Thunderchild First Nation

Learning how to overcome training and education barriers and manage land use, harness Treaty rights, and explore partnerships with like-minded settler and First Nation communities is essential for a First Nation to move into the industry, suggests Soonias. He also points to a specific advantage – youth in Indigenous communities.

“We have a tremendous opportunity to leverage young people in our communities,” said Soonias. “I think we’re going to see some different programmes be offered in schools as our communities start to look at how to inspire our next generation of farmers.”

“Because it’s not just about how do we do this today,” said Soonias. “It’s how we make sure the land will be here and available for our kids? And how do we make sure our kids are getting involved today so that their kids and seven generations from now have that renewed history and community knowledge that they can pass on?”

It’s a question of ownership

The question around land – who owns it and what a person can do with it – remains a challenge for Indigenous communities. Technically, reserve land is Crown land designated exclusively for use by First Nations. In a sense, Canada holds the land in trust. So leveraging financing or parcelling out the land to individuals can be problematic.

Still, Indigenous farms are growing, and communities find ways to make this odd legal arrangement work to their advantage. Soonias says participating in agriculture to retain cultural and traditional practices — like being stewards of the land — could lead to innovative business models and creative marketing opportunities.

Doing Agriculture Differently

“There’s a different connection to the land, the use and the management and stewardship of the land,” said Soonias. “And there’s different things that arise out of that.”

Soonias says this unique relationship with the land means broadening the definition of agriculture to include things like forestry management. Country foods, gathering medicines and mushrooms, or grassland reclamation to restore native prairie ecosystems could all fit this definition of agriculture and lead to innovative business models, like co-operatives.

“There’s natural herbs and medicines, mushrooms – chaga and morels – that are only available in certain times and often during the regeneration of the forest [after a fire],” said Soonias. “So, there’s some interesting things I think we’ll see in those spaces as we look at our communities harnessing our traditional knowledge in agriculture.”

Soonias notes that managing intellectual property rights in this space will be a challenge.

“Looking at how to harness intellectual property rights, while also being mindful of how to protect those tools are going to be some big questions that our communities face as they enter some of these areas,” said Soonias.

Where to Start

For communities wondering where to start, Soonias says the most significant opportunity is figuring out how to monetize your land in a way that best suits your community.

“Whether you’ve got 100,000 acres or you’re in the forest or Precambrian shield, our communities are stewards over vast tracts of land and water. So there’s a natural connection between the existing resources and this opportunity in the agricultural sector,” said Soonias. “But it’s at the infancy stage.”

Soonias suggests starting by asking a lot of people a lot of questions. Talk to an agronomist, get a feasibility study done, and see what your neighbours are doing. Plus, explore partnerships — settler and Indigenous — and research business models, such as co-operatives.

Take Advantage of Available Resources

To take advantage of this opportunity, Soonias points to several resources. He suggests using the numerous supports available, like FCC, CAHRC, Co-operatives First, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Indigenous Pathfinder Service. Also, consider contacting your Ministry of Agriculture, Export Canada, Indigenous Services Canada, and Western Economic Diversification.

And don’t limit yourself to production and livestock. Explore value-add, vertical integration opportunities, and unique and niche product marketing.

“Things are really aligning in the sector, whether it’s Farm Credit Canada, or communities themselves, academia, nonprofits, and other industry stakeholders, each are altering their lens towards what the opportunity is, and how we can support our Indigenous communities’ economic development engines to really ramp up and be successful in this space.”

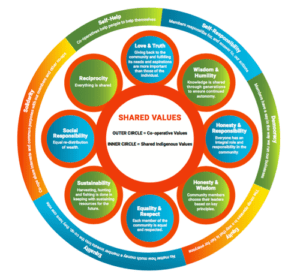

How Co-operatives First fits in

The co-op model has a role to play in Indigenous agriculture. Whether it’s joint equipment purchasing, global marketing opportunities, employee ownership, or multi-stakeholder investments, if you have an idea you would like to explore, contact us. We would love to look at the feasibility of the business alongside you.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

For more information on Farm Credit Canada’s survey, watch Shaun Soonias’s presentation to Cando HERE.

To learn more about the opportunities for Indigenous communities in agriculture, check out Shaun Soonias’s FCC colleague, Jesse Robson, presenting to Cando HERE.