Producer co-ops are a model we don’t hear discussed much anymore. Today, much of the awareness of co-operatives is fuelled (no pun intended) by consumer co-operatives with recognizable brands and widespread local support. This wasn’t always the case.

As Brett Fairbairn details[1], producer co-operatives were foundational to the survival of settlers and growth of western Canada. By 1900 there were over 1,200 co-operatively owned creameries (dairy co-ops) across Canada. But it was grain farmers that took the producer co-op and made it large scale.

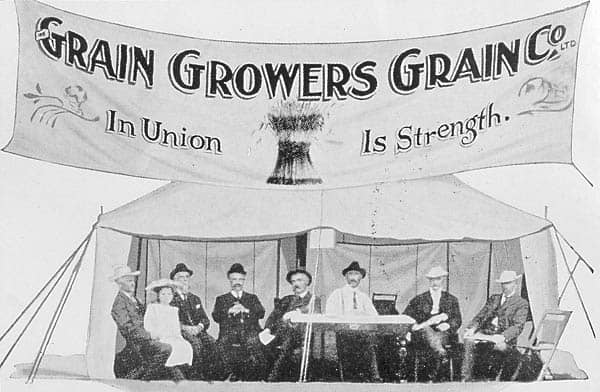

Grain Growers. Grain Co., a co-operative of farmers in Saskatchewan that was the precursor of the United Grain Growers.

In 1906, the Grain Growers Grain Company incorporated and pool marketing began building momentum. In no time, the Pool system was one of the most recognizable brands in western Canada. Eventually, they became publicly traded companies and were acquired by other firms. (Similar to what we see happening today with Alberta’s Rural Electrification Associations.)

Industry growth and increased support for grain farming – particularly in areas of market access, legislation and taxation – allowed producers to grow into large businesses and operate with more independence, decreasing the need for co-operative solutions in this sector.

Does this mean we’re done with producer co-ops? Not quite.

Though we don’t always notice producer co-operatives in the marketplace, that doesn’t mean they aren’t around and doing great work.

Here’s a few examples of producer co-ops making an impact on local, national, and global economies.

Hiding in plain sight

One of Canada’s largest co-operatives, Gay Lea Foods, notes on their website: “It might surprise you to know that Gay Lea Foods is a co-operative owned by over 1,200 farmers.” Most consumers, as Gay Lea suggests, are unaware that many of their favourite products are produced by co-ops.

Household names like Ocean Spray or Sunkist are 100+ year old co-operatives that have brought hundreds of farmers together to co-operatively produce value-added products.

This well-known yogurt brand is distributed by Ultima Foods, a subsidiary of Agropur – Canada’s second largest dairy producer and a producer-owned co-operative. SOURCE

This well-known yogurt brand is distributed by Ultima Foods, a subsidiary of Agropur – Canada’s second largest dairy producer and a producer-owned co-operative. SOURCE: https://www.iogo.ca/en/products/

Canada’s second largest dairy producer, Agropur, is co-operatively-owned and promotes well-known brands, such as IÖGO, Central Dairies, Scotsburn, and Natrel. The USA’s largest dairy producer, Dairy Farmers of America, is also co-operatively owned, and produces nearly 38 billion pounds of milk each year.

So, what about western Canada? Producer co-operatives across western Canadian continue to be leaders in food production.

Here’s a few examples:

- Granny’s Poultry Co-operative is owned by over 180 egg and poultry producers in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

- BC Livestock Producers Co-operative Association has been owned and operated by BC ranchers since the 1940s and has over 2000 members.

- Hams Marketing Services Co-operative represents over 200 pork producers in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and provides marketing and risk management services.

- Red Hat Co-operative in southern Alberta delivers fresh produce to retailers across western Canada daily and have over 50 grower members.

Innovations on the model

To encourage investment in agriculture and create good paying jobs in rural areas, states and provinces in North America introduced legislation for new generation co-operatives. The model originated in California and became successful in the mid-western states through the 1990s. It was adopted by Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in the early 2000s.

New generation co-operatives maintain some traditional characteristics of producer co-ops including one member one vote, patronage-based distribution of profit, and being member-owned and controlled. Some distinct differences include shares carrying delivery rights, restricted membership, the ability of individuals to hold varying levels of equity through investment shares, and not having to use the word ‘co-op’ or ‘co-operative’ in the organization’s name.

Some uses of this model include the Alberta Egg Producers Co-op that represents over 100 producers, the North American Bison Co-operative that processes over 10,000 head of bison per year sourced from over 300 independent ranchers, and Westlock Terminals, comprised of 11 farmers and local investors that acquired the terminal in Westlock, AB when a large grain company pulled out of the region.

Aligning economic and environmental sustainability

For the eight BC fisheries that are members of the River Select Co-operative, working together adds value to their products (fish) in a number of ways. The co-operative creates efficiencies, which reduces costs for the individual fisheries and provides streamlined marketing. This increased product offering and capacity allows the fisheries to target high-value markets, creating better returns for the co-op’s member fisheries.

The fishers from these fisheries also all value the natural environment, and care deeply for the communities they operate in. Dedication to these values is why the co-op practices selective harvesting. Selective harvesting helps ensure the sustainability of their fish resources. The goal of this sustainability is both a long-term business and economic goal, but also an environmental one. The two go hand-in-hand, and the co-operative helps the fisheries advocate for and promote these values with a united voice.

Marketing Art

Opportunity for new producer co-operatives can be found at craft fairs and tradeshows all over Canada. Indigenous artists produce beautiful products, but often struggle to access dependable markets or receive adequate return on their sales. Traveling to a tradeshow consumes a lot of resources for a small entrepreneurial artist. By creating marketing, logistic and administrative efficiencies through forming a co-operative, these small businesses can organize to create a co-operative that should increase their returns over time, create more time for producing work and expose their products to broader audiences.

Bear Drummer by Leo Napayok. SOURCE: Canadian Arctic Producers

And there are examples of co-ops like this working. Since the mid 20th Century Indigenous artists have recognized the value of co-operating, pooling resources and presenting a united front to market their work, access better purchasing arrangements, and introduce their work to a global audience. Dorset Fine Arts and Canadian Arctic Producers provide good examples of this type of collaborative effort amongst Inuit artists.

The Future

As communities grow and economies evolve, businesses and ideas emerge from new places. Growing population, economic and community strength, and a corresponding increase in sovereignty within some Indigenous communities, has sparked new conversations about accessing markets and enhancing economic development.

One of our recent blogs highlights an example. The Okanagan Indian Band is planning to use the co-operative business model and their land to be a “high supplier [in] the food chain worldwide.” Nations across the west are interested in forming producer co-ops to create economic growth through agriculture and economies of scale.

So, no, we’re not done with producer co-ops. They may often be out of sight, but producers, in every sense of the word, can benefit by co-operating, creating efficiencies, and adding value to their products. Operating in isolation may seem easier, but it isn’t always the best option. Whether increasing market share or accessing new markets, producer co-ops have an important and valuable role to play in Canadian and First Nation economies – especially rural and remote economies.

If you want to learn more about producer co-ops or how to start one, contact us.

[1] Brett’s chapter: Brett Fairbairn (2009), “Canada’s ‘Co-operative Province’: Individualism and Mutualism in a Settler Society, 1905 to 2005” in Jene M. Porter (ed.) Perspectives of Saskatchewan. University of Manitoba Press.

Written by

Written by