The rising interest in Indigenous co-operative development

There is a lot of momentum and increasing interest in the issues and needs around Indigenous co-op development in western Canada. It is a conversation that is both new, and very old within co-op development circles.

Last fall, the Saskatchewan Co-operative Association, in partnership with the Saskatchewan First Nations Economic Development Network, created a unique, made-in-Saskatchewan resource, Local People, Local Solutions: A Guide to First Nation Co-operative Development in Saskatchewan.

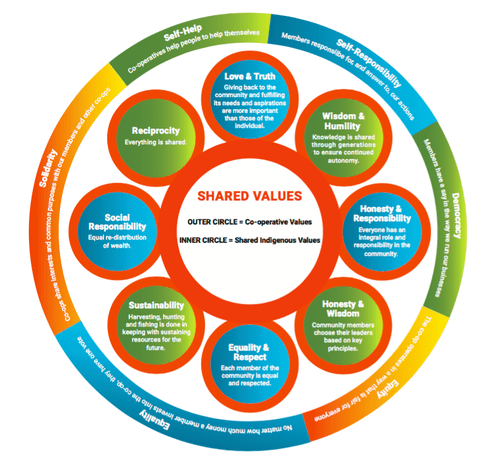

It’s a handbook that explores the synergies between First Nations culture and worldview, and the co-operative model. It also operates as a how-to manual, helping Saskatchewan’s First Nation communities learn about co-operatives and find ways to successfully use this business model to solve local issues. Based on consultations, particularly with elders, the resource is a must for those working in Indigenous co-operative development.

Another resource, from Manitoba, is Building Indigenous Co-operative Capacity: A Guide to Co-operative Development. While focused primarily on Winnipeg’s Indigenous community capacity around the co-operative model, this new resource guide echoes the work of the Saskatchewan group, while focusing on Manitoba. Extensive consultations, identifying opportunities, and finding champions were all part of the project. Again, Indigenous value systems, particularly the long history of collective ownership, are embedded.

Turning collective ownership to co-operative ownership

One of the strengths — and similarities — between co-operative and collective ownership is the critical role of local leadership, local power, and local say. While collective and co-operative ownership aren’t quite the same, their similarities can work in concert.

Recent research from the University of Saskatchewan’s Co-operative Innovation Project examines some of the best practices, as well as the more thorny questions and considerations that can come up within Indigenous communities when working with a co-op developer to build new businesses, even (and sometimes especially) with businesses using the co-operative model. Finding ways to include, even embed, existing governance structures into the co-op is critical; addressing politics, leadership, the role of elders, and adopting cultural viewpoints as part of the co-operative business model are key.

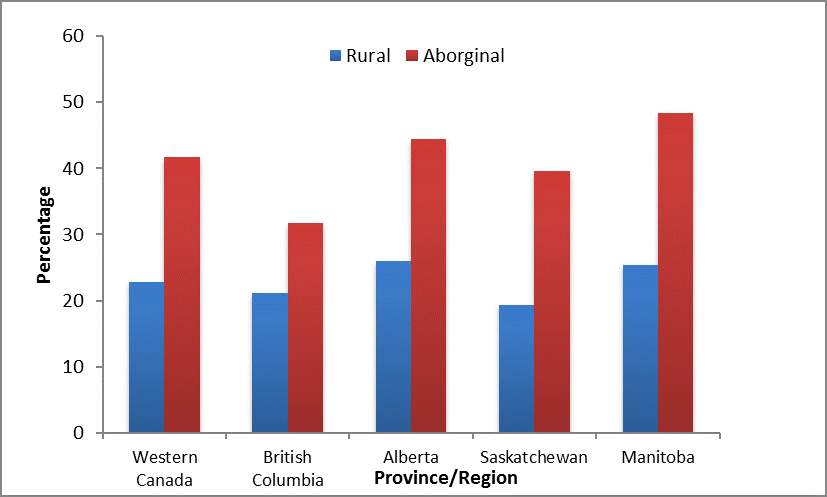

There is an educational component. In that research project, just over 40% of Indigenous survey respondents declared no knowledge of the co-operative model.

One of the findings of the Co-operative Innovation Project is that the co-operative model may find more traction, and be a tool that effectively addresses governance issues, when used beyond the band level.

This arena can be where multiple bands work together, or a mixture of bands and nearby municipalities, or where Tribal Councils or similar networks work together to create change.

A great example of this use of the co-op business model comes from Saskatchewan, with the recent Saskatchewan First Nations Technical Services Co-operative. Established in 2015, the 74 Saskatchewan First Nations came together to form a co-operative. Aiming to address technical service needs (such as housing inspection, water treatment, engineering, and so forth) on reserve, this co-operative business structure solves the governance issue that the First Nations leaders identified: local ownership, not a top-down ownership. In many ways, this use of the co-op model mimics second- or third-tier co-op ownership, or a co-operative that is owned by other co-ops or businesses.

Indigenous co-op development has an important past — and future

There remains a deep history and excellent current use of the co-operative model within First Nations, Metis, and Inuit communities in Canada. Possibly the best-known example is Arctic Co-operatives. At the root of Arctic Co-op’s success is local ownership, but their earliest history speaks to the role of local-level co-op development work, in part by the federal government. It also showcases the critical importance of language: much of the earliest community-level work to build co-operatives across the North recognized the role of language and culture, and created training modules and documents in local languages.

While the Canadian Co-operative Association and all of the above groups have been working hard to foster increased use of the co-operative model in Indigenous communities, including devising funding mechanisms to support groups, there remains work to be done. For example, there are intricacies to navigating the legal apparatus between provincial legislation around co-ops, local governance within First Nations, and the Indian Act. Storytelling around existing, past, or potential future co-ops is needed. Connecting Indigenous mentors with growing co-ops is part of the puzzle. Finally, asking Indigenous communities to identify and explore their needs, and seeing where and when those needs can be met using co-ops, is a great place to start for Indigenous co-op development.

Written by

Written by